Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome is a lung injury specific to critically ill patients and manifested in a specific form. A major cause of morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients, ARDS is a syndrome of diffused lung inflammation and oedema ultimately leading to respiratory failure.

Understanding its causes deeply and trying new treatment options may be the key to reduce mortality due to ARDS.

The Indian landscape of ARDS: Incidences, Etiology and Risk Factors.

Tropical infectious diseases in India showcases higher incidences of ARDS with a different a etiology.

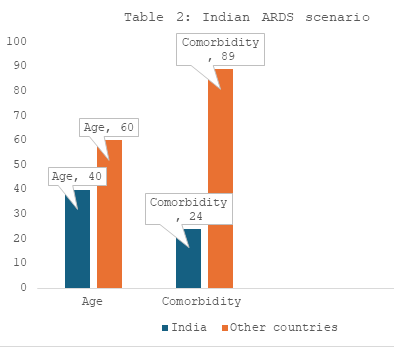

The epidemiological profile of patients suffering from ARDS in India are as follows:

- Mean age group in India is 39 to 42 years as opposed to western countries with age of 60 years in ARDS.

- Young working population is more prone to environmental exposure to vector-borne tropical diseases owing to its location.

- High comorbidity is significantly seen in nonsurvivors and especially in places such as Boston, not in India.

- Comorbidity in Indian patients is less as compared to other countries - Gives them a fighting chance.

- In India, only 24% of cases had preexisting comorbid illness while in Japan, 89% patients had some form of comorbidity.

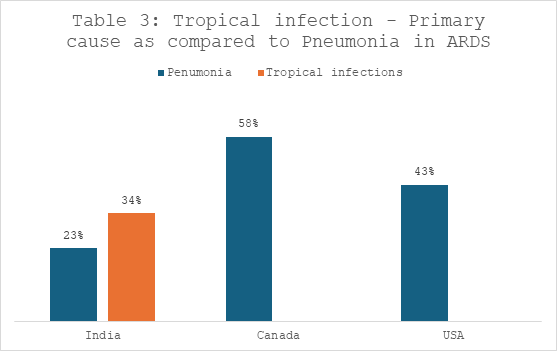

- In 90% of the patients, the cause for ARDS was infections.

- Tropical infections such malaria, leptospirosis and malaria with dengue cases were cumulatively higher than cases of pneumonia for secondary infections to ARDS.

- In other countries such as Canada and USA, pneumonia was the most common cause of ARDS infection (58% and 43% respectively).

- Older age (≥65 years old).

- High fever (≥39 °C).

- Lymphocytopenia (as well as lower CD3 and CD4 T-cell counts).

- Elevated end-organ related indices (eg, AST, urea, LDH).

- Elevated inflammation-related indices (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and serum ferritin).

- Elevated coagulation function–related indicators (PT and D-dimer).

- Treatment with methylprednisolone decreased the risk of death.

Risk factors that influence outcomes for ARDS patients:

As per the LUNG SAFE study, ARDS appears to be under-recognized and under-treated. It is found that the hospital mortality from ARDS is a significant 40%.

- The following were independent factors that increased the risk of mortality in ARDS patients:

- Patients with higher APACHE II score (designed to calculate severity of ARDS) (APACHE II score >20).

- Major cause of mortality – Complicating organ failures such as

- Acute kidney injury.

- Liver failure.

- Heart failure.

- MODS.

- Hemodynamic instability - The presence of MAP <65 mmHg (mean arterial pressure) indicates cardiovascular failure and relates closely to survival.

- High lactate level is depicts metabolic acidosis, predictive of acute lung injury in severely traumatized patients.

- The variable factor affecting mortality in ARDS patients is a higher driving pressure. Airway driving pressure is the only variable ventilation related to the survival and studies say that patients with a driving pressure (i.e., Pplat-PEEP) of more than 14 cmH2O on day 1 showed worse outcomes in ARDS and associated with an increased risk of death.

Risk factors for a prolonged duration of mechanical ventilation:

It is proven that patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation may have increased risk of infection and higher hospitalization cost, as well as experience decreased life quality.

The following points affect the duration of mechanical ventilation.

- The factors that influence duration of mechanical ventilation are directly related to the lung.

- More severe ARDS needs a prolonged ventilation time.

- The presence of VAP (Ventilator-associated pneumonia) may complicate the outcome of ARDS. However, this is a risk factor for prolonged ventilation not for ARDS survival itself.

- Comparing the risk factors for survival of ARDS, patients with lower lactate level, higher pH, higher BE and one organ failure (compared with multiple organ failure) required prolonged duration of mechanical ventilation as compared to reverse parameters which resulted in higher mortality rate and shorter duration of mechanical ventilation.

Highly complex and heterogeneous nature of ARDS makes it difficult to chart a perfect pathophysiology, although lot of advancements has happened over the years. Phenotyping helps in understanding and simplifying this heterogenous nature of ARDS.

Alveolar–capillary barrier injury – The key to understanding ARDS pathophysiology.

Normal alveolar-capillary barrier – composed of normal epithelial cells and capillary endothelial cells.

Injury to the barriers is a characteristic typica of ARDS and results in physiological abnormalities while the severity of the damage is important aspect to gauge survival of patients.

Changes in Epithelium

- Mild oedema formation.

- Disrupted tight junctions.

- Decreased surfactant production (increased chances of secondary infections).

- Impaired sodium and chlorine transport.

- Mild glycocalyx shedding.

- Activated epithelial cells secrete chemokines and express adhesion molecules.

Changes in Endothelium

- Disrupted tight junctions.

- Paracellular fluid leakage from plasma.

- Injured endothelial glycocalyx.

- Upregulated adhesion molecules.

- RBCs might be injured transiting the capillary.

- Adherent Poly mononuclear cells.

Changes in Epithelium

- Severe oedema formation.

- Severe disruption of tight junctions.

- Epithelial necrosis.

- Hyaline membrane formation.

- Absent sodium and chlorine transport.

- Glycocalyx shedding.

- Increased chemokines and adhesion molecules.

- RBCs in airspace.

Changes in Endothelium

- More severe endothelial disruption with transit of fluid out of the capillary.

- Loss of endothelial glycocalyx.

- RBC injury.

- PMN transmigration.

- Platelet microthrombi.

Consequences of injury to the capillary-alveolar barrier –

Injury to the capillary-alveolar barrier causes Alveolar flooding.

Alveolar flooding - causes sever gas exchange impairment and decreased lung compliance.

Activation of procoagulant pathways on the lung’s endothelium – leads to lung microvascular thromboses leading to increased dead space which results in severe gas-exchange impairments leading to higher mortality.

Severe damage to the microvascular bed and thrombosis may lead to pulmonary arterial hypertension and acute right ventricular dysfunction, which have poor clinical outcome in ARDS settings.

Role of Mechanical ventilation in manifesting lung injury - The best course of action Read More

ARDS in children (Pediatric ARDS):

- Less common in children and less likely to lead to death, the estimated incidence being 2.0 to 12.8 cases per 100,000 person-years.

- The estimated mortality rate is 18% to 27%.

- Risk factors in children are similar to those in adults - direct and indirect lung injury.

- Causes of ARDS in children:

- Viral respiratory infection - most common cause.

- Drowning.

- Treatment recommendations for children with ARDS:

- These are mostly like those for adults.

- The recommended tidal volume is 5 to 8 mL per kg of predicted body weight (3 to 6 mL per kg in those with poor pulmonary compliance).

- This should be at or below the physiologic tidal volume for age and weight.

- Recommended PEEP values for children: Ten to 15 cm H2O for severe ARDS, and higher if the plateau pressure allows and if needed.

- The plateau pressure recommendations: Should be kept at or below 28 cm H2O. May be allowed to reach 32 cm H2O for those with reduced compliance. Recruitment maneuvers are recommended in severe cases. High-frequency oscillatory ventilation can be considered for children whose plateau pressures rise above 28 cm H2O when reduced chest wall compliance is not a factor.

- The arterial pH may be allowed to go as low as 7.15 in conjunction with a lung-protective ventilation strategy that incorporates low tidal volumes.

- As with adults, children with ARDS should be evaluated daily to determine if they are eligible for ventilator weaning.

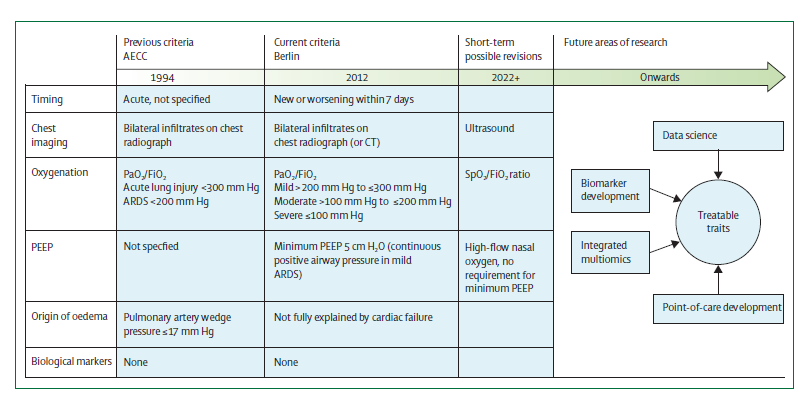

First described in 1967, ARDS was defined with characteristics-

- New onset hypoxemia refractory to supplemental oxygen.

- Bilateral infiltrates on chest radiograph.

- Reduced respiratory system compliance.

After proposing the lung-injury score, in 2012 the Berlin definition was proposed.

The timeline of defining ARDS and its future areas.

The Berlin definition of acute respiratory distress syndrome is as follows:

- The onset should be within a week time.

- Chest imaging: Presence of bilateral opacities in the chest imaging not completely explained by effusions, collapse, or the nodules.

- Respiratory failure not explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload; ruling out hydrostatic oedema if no risk factor present is required based on objective assessment.

- Oxygenation is calculated based on the ARDS classification as mild, moderate or severe using the PaO2/FiO2 ratio.

200 mmHg > PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg with positive end-expiratory pressure or continuous positive airway pressure ≥ 5 cm H2O ( delivered non-invasively).

100 mm Hg > PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 mm Hg with positive end-expiratory pressure ≥ 5 cm H2O.

PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 100 mmHg with positive end-expiratory pressure ≥ 5 cm H2O.

Recommendations of expanding the Berlin definition by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines:

- Include HFNO with a minimum flow rate ³ 30 liters a minute.

- Use arterial oxygen tension (SpO2/FIO2), as measured with pulse oximetry, for ARDS diagnosis and assessment of severity if SpO2 is less than or equal to 97 percent as an alternative to arterial gas measurement.

- Retain bilateral lung opacities (areas of the lung that appear more opaque) for imaging criteria, but add ultrasound as an imaging modality, especially in resource-limited areas.

- In resource-limited settings, remove requirement of require positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP; the positive pressure that remains in airways at the end of exhalation), oxygen flow rate, or specific respiratory support devices.

ARDS phenotyping – are there any benefits to outcomes?

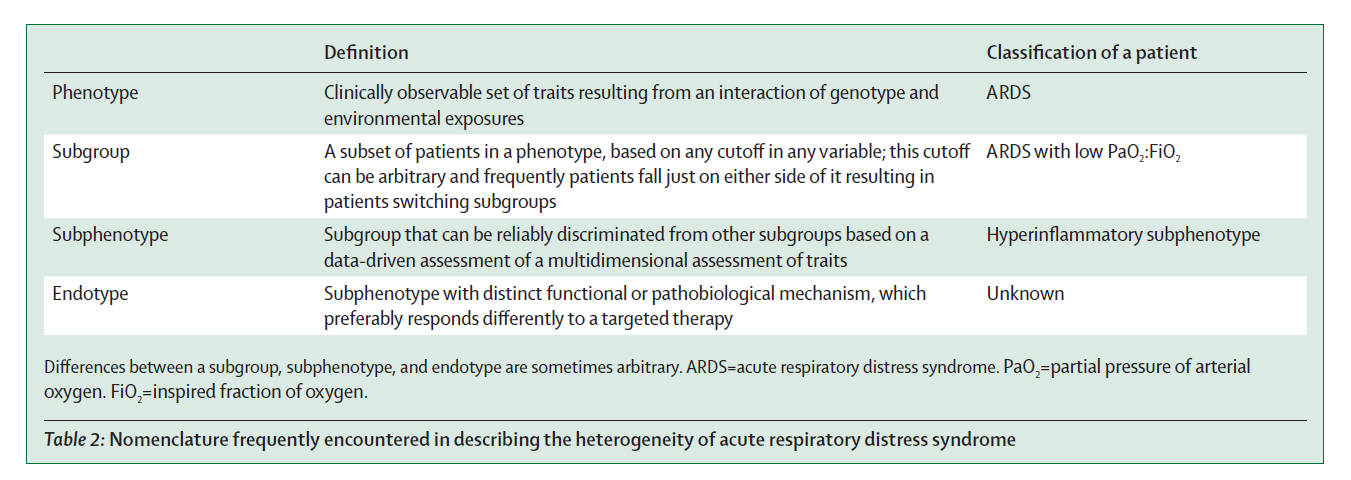

A substantial heterogeneity is observed among patients fulfilling ARDS criteria. The subcategorisation of these patients further into more homogeneous groups is referred to as phenotyping, the benefit of which is a more targeted intervention can be delivered. Based on clinical, imaging, physiological, or biomarker data, ARDS is split into following subgroups (table below) –

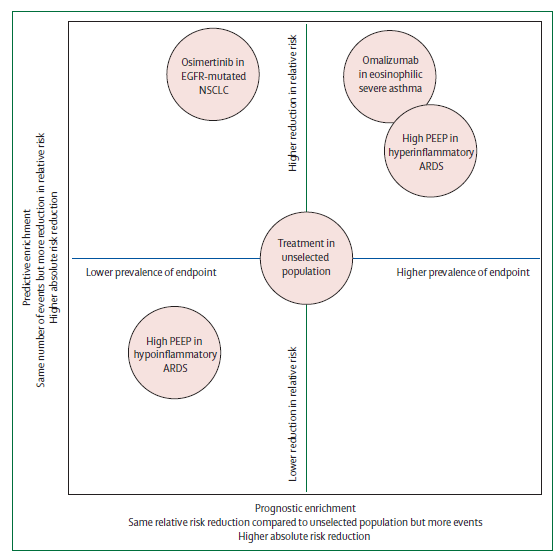

Phenotyping may increase understanding of ARDS pathophysiology and used to improve outcomes in two ways –

- Preferential inclusion of a subphenotype with a higher likelihood of developing the primary outcome results in increased statistical power (Prognostic enrichment).

- Selective inclusion of patients with an endotype who are randomly assigned to receive an intervention that targets that endotype, will probably benefit more than an unselected population (Predictive enrichment).

Subphenotyping of ARDS will only result in better patient outcomes when prospective randomised controlled trials find beneficial effects of subphenotype-driven treatment strategies.

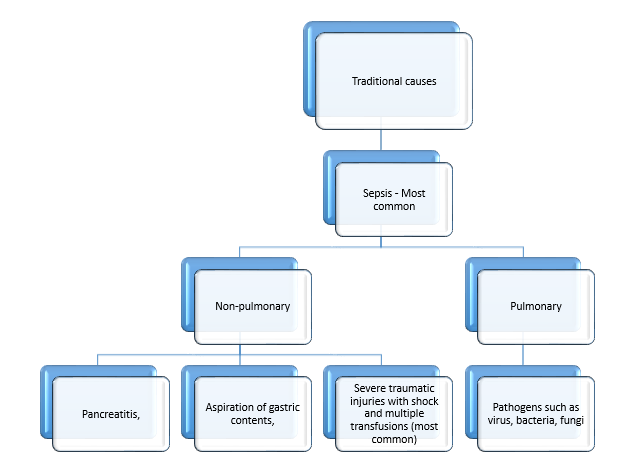

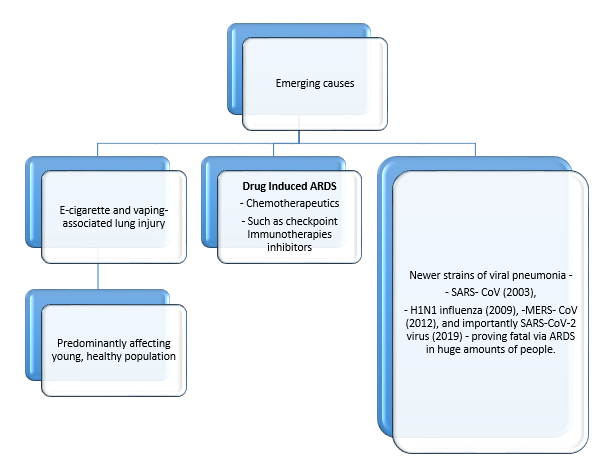

Sub phenotyping by cause:

ARDS can be incited by different causes that may be pulmonary or extra-pulmonary. Since extrapulmonary causes of ARDS affect the whole lung via endothelial dysfunction rather than the more localised injury expected in a direct pulmonary cause, a more diffuse injury pattern is common, which might result in a better response to lung recruitment strategies such as increased positive end-expiratory pressure.

There has been substantial progress to prevent hospital - acquired ARDS for specific causes such as:

- Plasma transfusion from female donors rather than male donors - major risk factor for transfusion-related acute lung injury and hence, the use of male-only fresh-frozen plasma has substantially decreased transfusion-related acute lung injury.

- Patients with severe traumatic injuries are at high risk for ARDS, probably due to additive injury from haemorrhagic shock, mechanical ventilation, resuscitation, and multiple blood transfusions.

Role of phenotyping in treatment of ARDS:

The heterogeneity of treatment eect is apparent from researching about ventilatory strategies in ARDS, suggesting there could be phenotypes (or treatable traits) to direct personalised ventilatory strategies.

- Study showed that patients with low respiratory system compliance might be more likely to benefit from low tidal volumes and low driving pressures, whereas patients with high compliance were predicted to benefit more from low respiratory rates.

- In a trial (EPVent-2) investigating oesophageal pressure-guided PEEP in ARDS, a differential effect on mortality dependent on disease severity as determined by the APACHE-II score was seen.

- Hyperinflammatory and hypoinflammatory subphenotypes of ARDS have also been reported to respond differentially to PEEP strategies.

- The LIVE trial investigating personalised mechanical ventilation tailored to lung morphology in patients with ARDS, highlighted the need to align phenotypes with personalised ventilation strategies.

- The study showed that patients receiving a ventilator strategy misaligned with lung morphology had substantially high mortality rates.

Pneumonia is a leading cause of ARDS, and distinguishing patients with uncomplicated pneumonia from those with ARDS can be a diagnostic challenge.

Patients with ARDS represent a subset of a broader population of acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. The key difference between ARDS and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure is the requirement for bilateral infiltrates on chest imaging.

In ARDS, it is essential to identify the cause of lung injury to devise a suitable a etiological and symptomatic treatment plan.

- The initial systemic microbiological assessment should include identification of the pathogen causing ARDS, especially pneumonia-causing pathogens as the latter is the leading cause of ARDS.

- The work-up includes blood cultures, urinary antigen testing, serologic tests and microbial sampling of the lung.

- Fiber optic Broncho alveolar lavage (BAL) is a preferred tool for ARDS patients because it helps to obtain large amounts of intra-alveolar material.

- In ARDS patients with fever, first, ventilator acquired pneumonia pathogens should be ruled out following extrapulmonary infections should be checked and finally any non-infectious process should be evaluated.

- Once the classical risk factors are ruled out, BAL fluid cytology, chest CT scan and specific immunologic marker examinations should be performed to further identify the causes.

- In case of suspicion of intra-abdominal sepsis, CT scan remains to be an important test.

- Lung biopsy is considered if these diagnostic tests do not give a clear cause of ARDS to rule out malignancy.

- Lung ultrasonography helps to assess the left and right ventricular functions as well identifies pleural effusions or a pneumothorax.

Emerging tools in research for improving diagnosis in ARDS:

Patients with ARDS represent a subset of a broader population of acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. The key difference between ARDS and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure is the requirement for bilateral infiltrates on chest imaging.

Various tools have been investigated to improve the reliability of ARDS diagnosis. Some of these are:

- The Radiographic Assessment of Lung Oedema score: Uses a visual assessment of four quadrant consolidation and infiltrate density, has been shown to have good intraobserver reliability and high diagnostic accuracy for ARDS.

- Visual assessment score: Correlates with important clinical outcomes including mortality and duration of intensive care unit stay.

- Artificial intelligence technology: Uses deep convolutional neural networks trained to recognize findings on imaging.

ARDS Detection Tool: A tool shown to accurately identify bilateral airspace consolidation consistent with ARDS in research settings but requires further validation before clinical use.

- Simple bedside tools of use in resource-limited settings, and outside the traditional intensive care unit – Results from the COVID-19 epidemic:

- Ultrasound imaging is emerging as a safe, inexpensive, tool for the evaluation of ARDS and could be implemented as a diagnostic imaging modality for pulmonary infiltrates with proper training.

- A ratio between oxygen saturation, measured by pulse oximetry, and fraction of inspired oxygen (SpO2/FiO2) is an attractive alternative to a ratio between partial pressure f arterial oxygen and FiO2 (PaO2/FiO2) ratio due to its availability and safety.

However, these tools are not without limitations as the ultrasound may overestimate ARDS while pulse oximetry could cause disparities in the identification of occult hypoxemia due to skin color.

Differential diagnosis in ARDS:

In many cases, ARDS must be differentiated from congestive heart failure and pneumonia. Following table differentiates depending on results of certain diagnostic criteria:

Factors That Distinguish ARDS, CHF, and Pneumonia.

| Distinguishing Factor | ARDS | CHF | Pneumonia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | |||

| Dyspnea | + | + | + |

| Hypoxia | + | + | + |

| Pleuritic Chest Pain | + / - | - | + |

| Sputum Production | + / - | - | + |

| Tachypnea | + | + | + |

| Signs | |||

| Edema | - | + | - |

| Fever | + / - | - | + |

| Jugular Venous Distension | - | + | - |

| Rales | + | + | + |

| Third Heart Sound | - | + | - |

| Studies | |||

| Bilateral Infitrates | + | + / - | + / - |

| Cardiac Enlargement | - | + | - |

| Elevated Brain Natriuretic Peptide Level | + / - | + | - |

| Hypoxemia | + | + | + |

| Localized Infiltrate | - | - | + |

| Pro,/Fio2ratio ≤ 300 | + | - | - |

| Pulmonary Wedge Pressure ≤ 18mm Hg | + | - | + |

| Responses | |||

| Antibiotics | - | - | + |

| Diuretics | - | + | - |

| Oxygen | - | + | + |

+ = present, - = absent, +/- = may or may not be present, ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome; CHF = congestive heart failure; Fio2 = fraction of inspired oxygen; PAo2 = partial pressure of arterial oxygen.